In our complex, information-rich, culturally diverse world, literacy is no longer just knowing how to read and write. Students need to understand and be proficient in these Five Essential Literacies to be successful in our global society:

In our complex, information-rich, culturally diverse world, literacy is no longer just knowing how to read and write. Students need to understand and be proficient in these Five Essential Literacies to be successful in our global society:

- Reading and Writing (the original literacy)

- Content Area/ Disciplinary Literacy (content & thinking specific to a discipline)

- Information Literacy (the traditional library curriculum)

- Digital Literacy (how and when to use various technologies)

- Media Literacy (published works—encompasses all other literacies)

As School Librarians we need to integrate at least one Library Literacy component into every class visit to the library, so I’m addressing each of these literacies in a separate blog post to offer suggestions and examples about how we might do that. My Part 1 blog post covered reading, so this post looks at Content Area/Disciplinary Literacy.

Many educators equate Content Area Literacy to structurally analyzing subject area text to read more proficiently. But we need to take this a step further, to help students identify with the discipline itself. Disciplinary Literacy means students can think like a scientist, or a mathematician, or an historian, or a musician, or an artist. School Librarians are in a unique position to construct lessons that infuse reading, writing, thinking, and communication skills specific to each discipline’s vocabulary, concepts, and methods.

INTEGRATE DISCIPLINARY LITERACY

When I simplified my Library Orientations with ELA classes to focus solely on reading, I actually created opportunities for other subject-area Library Lessons where students would learn library skills in context and be more likely to remember and apply what they learn. Subject-area teachers see value in these kinds of library lessons, so they are amenable for more lessons as the year progresses. They share the positive experience with others, who are then motivated to collaborate with us. Here are 5 examples of how I integrate disciplinary thinking for various subject areas into my Library Lessons.

Dewey Decimal Numbers with Math Classes

My listserv posts suggest that School Librarians often struggle with presenting Dewey Decimal Classification in a meaningful way. Why not invite Math classes to the library? Dewey Decimals give them a curricular reason to visit, especially with a hands-on activity that practices identifying and using decimal numbers. My students love coming to the library with their Math class—it’s new and different so they’re excited! Math teachers like a fun, non-graded review where they can see which students are having trouble with decimals, so they come to me to schedule their class visit!

My middle school Dewey Lessons activate prior knowledge of decimals to prepare students for their coming Math decimal unit, while teaching how decimals are used in the library. Their activity has them solve decimal problems to locate decimal-numbered books, because what’s important about DDC is teaching students how to USE it, not memorize it.

My 6g Dewey Lesson reviews decimal number place values and sequencing decimals, to prepare students for learning to add and subtract decimals. I tell students that when we get a new book in the library, we ask, “What is this book about?” The answer determines the Dewey number we assign to the book. We review how each place of a decimal number has a certain value—hundreds, tens, ones, tenths, hundredths, thousandths. Likewise in the library, each place has a value: a subject or topic of knowledge. As we move from left to right, each number denotes a more specific sub-topic of the one before it.

My 6g Dewey Lesson reviews decimal number place values and sequencing decimals, to prepare students for learning to add and subtract decimals. I tell students that when we get a new book in the library, we ask, “What is this book about?” The answer determines the Dewey number we assign to the book. We review how each place of a decimal number has a certain value—hundreds, tens, ones, tenths, hundredths, thousandths. Likewise in the library, each place has a value: a subject or topic of knowledge. As we move from left to right, each number denotes a more specific sub-topic of the one before it.

a- My 7g Dewey Lesson reviews adding and subtracting decimals to prepare students for learning to multiply and divide decimals. This lesson does take some preparation, but it’s worth it to see student partners scurrying around the library to locate their 2 Dewey-number books and having a wonderful time…in a Math class!

a - Even elementary students who have not learned decimals can put numbers in order:

- Create a set of picture cards that match those on Dewey shelf signs and put a corresponding Dewey number on the back, using only 3 digit ones for the itty-bitties. Distribute them on tables and have students pick a favorite Subject from their table, then use the number on the back to find a book on the shelf with that number.

- To help students understand that there are two parts to a Dewey number, create one color of cards with 3 numbers and another color of cards with a big dot & 1 or 2 numbers to the right of the dot. They can learn that each part is in separate numerical order, and that’s how you find the numbers. Students pair the cards, then find the Dewey Number on the shelf.

Because my Dewey Lessons focus only on locating Dewey numbers, students grasp that Dewey numbers listed next to search results in the online catalog tell them exactly where to locate the book on the shelf. I incorporate Subject searching the online catalog into Content-area lessons where it is more pertinent and better remembered.

Content-area Classes for Exploring Dewey Subjects

Integrating Dewey Subjects into related Content-area lessons is better than a generic standalone Dewey lesson because integrated lessons support classroom learning and are better remembered. For example, Science classes study the organization and classification of living organisms, and Dewey numbers follow that same disciplinary structure. My Library Lesson helps students make visible association between the Science content and Dewey bookshelf organization which reinforces their learning of the discipline’s vocabulary & content, and of library skills. I wrote about this lesson in an earlier blog post, and also about how Geography and Dewey organization of countries in the 900s is another subject lesson opportunity.

Online Databases with Social Studies & Science

My listservs often have lesson requests for teaching online subscription database services. Such lessons only have value when they are integrated into classroom subject activities. Early in the school year I have WebQuest lessons with Science and with Social Studies to introduce an online encyclopedia and 2 other databases that have the specific resources students need to complete their current assignment.

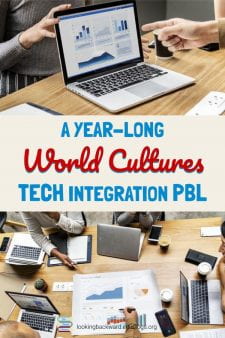

I created a unit with ongoing lessons for 6g World Cultures classes that help students think like economic analysts. I introduce an online service from which students choose demographic statistics of a few countries related to their unit and record them into a digital spreadsheet. I teach students how the spreadsheet can create a graph comparing one demographic across countries. For each new continent unit students add new countries and statistics to their spreadsheet, and I teach them to create a new kind of graph. (This is great technology integration, too.) By spacing lessons throughout the school year students are developing content/discipline literacy in Social Studies.

I created a unit with ongoing lessons for 6g World Cultures classes that help students think like economic analysts. I introduce an online service from which students choose demographic statistics of a few countries related to their unit and record them into a digital spreadsheet. I teach students how the spreadsheet can create a graph comparing one demographic across countries. For each new continent unit students add new countries and statistics to their spreadsheet, and I teach them to create a new kind of graph. (This is great technology integration, too.) By spacing lessons throughout the school year students are developing content/discipline literacy in Social Studies.

The culmination of this long-term lesson is an authentic activity: students act as “members” of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (www.un.org/ecosoc/), whose goal is to “conduct cutting-edge analysis, agree on global norms, and advocate for…solutions” to advance sustainable development. During library visits, student groups analyze their spreadsheets and create new graphs, then collaborate for a presentation on why a chosen country is most in need of development by the U.N. At the end of presentations, student “members” vote on which country the organization will support. This lesson furthers disciplinary thinking along with critical thinking and cooperative learning skills.

Disciplinary Literacy and Research Projects

6g Science classes visit our Outdoor Learning Center during their ecology unit to conduct various environmental analyses. As a culminating activity students participate in a 3-day “Science Symposium.” In their science classrooms, small group “Workshops” compare & consolidate their gathered data. Next day, class periods meet in the library for the “Conference” and 2-table groups analyze the environmental impact of building a factory on empty land adjoining the OLC property. They create a presentation for whether to approve it or not. Last day is the “Plenary Session” when a spokesperson for each group makes their presentation, then students vote on a “Recommendation to the City” for whether to grant permission for the company to build its factory. This is another example of building the Disciplinary Literacy students need to be successful with coursework and with future decisions.

In 7th grade Social Studies & English Language Arts we’ve made a dull immigration project and a so-so personal narrative into an authentic interdisciplinary project. “My Texas Heritage—How & Why I’m in Texas” has students learn the history of themselves the same way they learn the history of our State. It gives students a sense of identity (important for middle schoolers) and provides a personal understanding of conceptual factors that have brought people into the state.

As the School Librarian I teach research skills with a variety of primary and secondary sources, both in print and online—biographies, speeches, letters, diaries, songs, and artwork. In ELA they learn how to interview family members in person and through written requests. In Social Studies they learn to discern similarities and differences between historical events and the lives of their own family. Students create concise, well-written webpages to share information with family members, which forces students to thoroughly think through and edit responses to their research questions.

Students who share common events can group together for mock newscasts of “eyewitness” accounts, and discern that historical “truths” often depend on one’s point of view—a valuable lesson for studying history. This project develops multiple disciplinary literacies as students learn to think like historians, journalists, webmasters, and newscasters.

Students who share common events can group together for mock newscasts of “eyewitness” accounts, and discern that historical “truths” often depend on one’s point of view—a valuable lesson for studying history. This project develops multiple disciplinary literacies as students learn to think like historians, journalists, webmasters, and newscasters.

SCHOOL LIBRARIANS & CURRICULUM

It is apparent to me that the only way we School Librarians can integrate Content Area/Disciplinary Literacy into our Library Lessons is to become very familiar with the curriculum taught by our teachers. When we take to them a lesson plan that fully incorporates what they are doing in their classroom, they will be more willing to collaborate with us, knowing that the library visit is not only essential for learning the Subject-area’s content, but also for helping students think according to that Discipline.

This is the second entry in my series of blog posts on the 5 Essential Literacies for Students. I invite readers to offer comments and suggestions about any or all of these literacies.