Middle school—grades 6, 7, 8—is the most changeable time period for children. The student who leaves the building after 8th grade is very different from the 6th grader who entered the building 3 years earlier. And 7th grade? My principal says, “There’s a special place in heaven for 7th grade teachers.” I think it probably has padded walls.

Middle school—grades 6, 7, 8—is the most changeable time period for children. The student who leaves the building after 8th grade is very different from the 6th grader who entered the building 3 years earlier. And 7th grade? My principal says, “There’s a special place in heaven for 7th grade teachers.” I think it probably has padded walls.

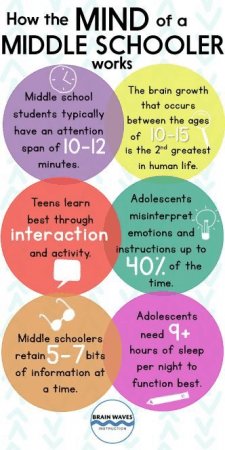

I believe understanding this stage of physical & mental development helps us adjust our expectations for the behavior of these 11-14-year-olds and create lessons that are appealing and engaging.

What do we know about adolescence & puberty? What is most common characteristic of 11-16 year olds? It is a time to ask questions & seek answers!!

6th GRADE

Our newbies, the 6th graders, are just beginning the transition from the concrete childhood mind to the abstract adult mind. They are still accepting of adult guidance, but because they are now more capable of reasoning, they want to know why they are being asked to do something. They’ve not yet grown out of their ‘elementary’ self and are still a bit fidgety, so lessons for these students need to be short, visual presentations broken up with small segments of physical activity.

Our newbies, the 6th graders, are just beginning the transition from the concrete childhood mind to the abstract adult mind. They are still accepting of adult guidance, but because they are now more capable of reasoning, they want to know why they are being asked to do something. They’ve not yet grown out of their ‘elementary’ self and are still a bit fidgety, so lessons for these students need to be short, visual presentations broken up with small segments of physical activity.

If you want to understand a 6th grader, visit a classroom during a testing session. It’s non-stop motion, hands, bodies, legs, fidgeting constantly. With all this movement, you’re sure the room must be infested with bugs.

7th GRADE

By 7g the body is now entering puberty, and everything—I mean every single cell—in a 7th grader’s body is connected to their mouth. They can’t do anything without talking—not walking, sitting, listening, watching, reading, writing, keyboarding, looking for a book, eating, or even breathing. If they are awake, they are talking.

For a real treat, stand outside a restroom when a single 7th grader is in there.

I guarantee they will be talking, even though they are the only one there!

For a 7th grader peers are everything so they want to do everything in pairs (bathroom, lunch, locker, nurse, office), but 7th graders are also “orphans”: parents are to be avoided at all costs. They’ll insist on Mom dropping them off a block from school in the pouring rain, just so no one sees them with a parent…which means telling them you’ll call a parent about behavior is met with disdain.

For a 7th grader peers are everything so they want to do everything in pairs (bathroom, lunch, locker, nurse, office), but 7th graders are also “orphans”: parents are to be avoided at all costs. They’ll insist on Mom dropping them off a block from school in the pouring rain, just so no one sees them with a parent…which means telling them you’ll call a parent about behavior is met with disdain.

And 7th graders are intellectually brain dead. Tasked with coordinating all the physical changes to their bodies, their brains can’t handle complex mental exertion, just like those alternating—albeit shorter—spurts of physical and mental growth when they were babies.

8th GRADE

The most startling change in middle school happens during the summer between 7g and 8g. When 8th graders appear in the fall, they’ve grown a foot and have become young adults. Their maturity is evident—they are less self-involved and more future-oriented—so are capable of complex critical thinking with global outcomes.

Most importantly, 8th graders expect us to treat them with dignity, but they bore easily and quickly, reverting to childhood shenanigans, so they need creative, independent activity.

MIDDLE SCHOOL LIBRARY LESSONS

For me, being a Middle School Librarian is the best grade level because teachers are still willing to bring students frequently enough for continuity of lessons and the kids are now old enough to use a wider variety of resources and technology tools. Also, these 3 years are a long enough period to scaffold lessons from novice to proficient, but a short enough period that integrating lessons into all subject and grade level curricula isn’t overwhelming.

We can teach the same lesson to all 3 grade levels, but the presentation and activities must be very different for each grade. We can plan a similar type of project, but offering different tools for the products opens up a realm of creative possibilities for librarians.

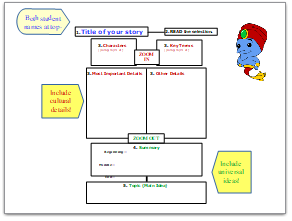

For 6g lessons I still offer lots of structure and step-by-step instruction. I establish a process or procedure, then use a similar structure for every lesson, gradually adding variety as the year progresses. For example, my 6g orientation and 6g Dewey lesson use the same activity, and my ELA literary text units all begin with the same “book buffet,” so the focus is on the different materials, not on explaining a new procedure.

For 7g lessons I regularly partner students, especially to have them “discuss.” We have to find interesting ways for them to recall prior knowledge and blend that into new material. For example, my 7g orientation has students partner up for a scavenger hunt to activate prior knowledge of the library and to spotlight some materials they weren’t likely to use before.

Since 8g students are 13 they are able to use more online tools. For example, my 8g orientation has students use smartphones to view video book trailers to interest them in topical books they may not have considered. I can also introduce them to a wider range of subscription database services than I could in previous grades.

We also need variation between grade levels when teaching information literacy skills. I’ve written about how I use my Library Lesson Matrix to scaffold Info-Lit lessons throughout subjects within a grade level, and embed subject standards and content vocabulary to support content literacy. My Matrix also helps me bridge the grade levels by using similar processes to introduce new Info-Lit skills and tools, and to develop independent learners.

DEVELOPING INDEPENDENT LEARNERS

Middle school content encompasses the transition from simple concrete lessons of elementary to the higher-level critical thinking that students are expected to use in high school. It’s the ideal time to develop independent learners, but we can’t expect our students to become independent learners by themselves—it’s a logical extension of having learned and practiced. We need to develop independence by design, not by chance, through scaffolded instruction and activities that allow students to practice in a gradually more independent manner.

Middle school students will not fully attain independence, but showing them how to become independent learners is part of our responsibility.

Student independence is relative to concepts studied, resources used, and maturity of the learner. One mistake teachers often make is to think that just because students can read, they can read and learn subject-area content with minimal further instruction. Actually, we need to provide instruction to specifically support content-intensive reading materials:

Student independence is relative to concepts studied, resources used, and maturity of the learner. One mistake teachers often make is to think that just because students can read, they can read and learn subject-area content with minimal further instruction. Actually, we need to provide instruction to specifically support content-intensive reading materials:

- teach reading and reasoning processes as a natural part of the curriculum

- bring in concepts from multiple curriculum areas

- guide independence relative to abstraction and complexity of materials.

We can do this if we organize instruction into 3 transitional types of activities: preparation, guidance, independence:

- Preparation gets the student ready for reading, through predictions, curiosity arousal, Conceptual Conflict (what if or how did that happen?), and anticipation guides.

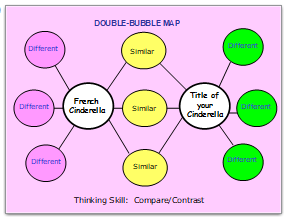

- Guidance activities like extended anticipation guides, graphic organizers, and self-generated questions teach students how to apply reading and reasoning skills. Self-questioning aids retention, and students need to be led through such metacognitive activities so it becomes automatic.

- Independence allows students to work on their own, applying what they’ve learned. Discussion models such as think/pair/share, accountable talk moves, and Socratic seminars give students a chance for interaction with peers, yet rely on the teacher’s guidance when needed.

Independence does not mean isolation; it has to do with who is in charge. We cannot be impatient for our students to be independent, nor limit the time they need for becoming independent.

Our middle school library lessons can incorporate these activities into each and every library visit. My Library Lesson Planner does that with Direct Instruction, Modeling/Guided Practice, and Independent Practice. When I show my completed Library Lesson Plan to a teacher, with their subject standards, content vocabulary, and these activities, they regard me as a teaching professional and are more willing to collaborate then and in the future.

Here are two resources which you may find helpful in developing lessons for middle schoolers:

- 4 Brain-Based Tips for Teaching Middle School

- Science of Adolescent Learning: How Body and Brain Development Affect Student Learning

SOME TEACHING “HELPERS”

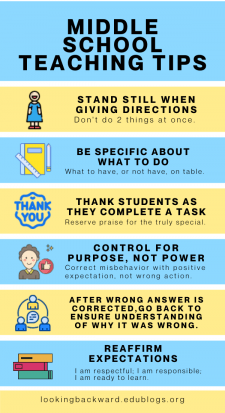

Middle school students can be a challenge. There are days when they aggravate us so much we’d like to ship them off to an island somewhere. Then there are joyful days when we can’t imagine teaching anywhere else! To help handle the day-to-day stresses—both ours and theirs—here are some general reminders I’ve learned over the years:

Middle school students can be a challenge. There are days when they aggravate us so much we’d like to ship them off to an island somewhere. Then there are joyful days when we can’t imagine teaching anywhere else! To help handle the day-to-day stresses—both ours and theirs—here are some general reminders I’ve learned over the years:

- Stand still when you’re giving directions (don’t do 2 things at once)

- Be specific about what to do (what to have on desk, what not to have)

- Thank them as they complete task, but reserve praise for what’s truly special or exceeds expectations (“Thanks for [behavior that meets expectations].”)

- Control should be for purpose, not power. Correct misbehavior with the positive expectation, not the negative wrong. (“We don’t do that in this classroom because it keeps us from making the most of our learning time.”)

- Go from student who gets it wrong to students who get it right, then back to student who gets it wrong by asking a follow-up question to make sure they understand why they got it wrong and understand why the right answer is right.

- Reaffirm expectations: I am respectful; I am responsible; I am ready to learn.