A school librarian may see young children every week, but the older students become, the less we see them, maybe only a few times a year. Fortunately, we have most of these students over a 3-5 year period, depending on whether we are an elementary, middle, or high school librarian.

A school librarian may see young children every week, but the older students become, the less we see them, maybe only a few times a year. Fortunately, we have most of these students over a 3-5 year period, depending on whether we are an elementary, middle, or high school librarian.

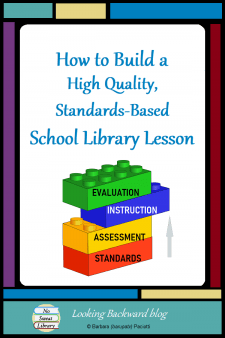

We can scaffold short lessons throughout the school year, so by the time students leave us, they’ve mastered what they need for their next stage of library use. The question is, how best to do that? How can we build high quality, standards-based library lessons? I’m here to tell you: DON’T start with library curriculum—start with everyone else’s curriculum!

CREATE A CURRICULUM MATRIX

School Librarians are masters at integrating Library Information Literacy Skills into any subject. To do that, we don’t need to know the depth of a subject as teachers do, but rather, we need to look at the breadth of subject curricula and determine when students are likely to benefit from a library lesson.

I’ve written about my Library Lesson Matrix and how I use that visual organizer to plan when each subject area needs a Library Lesson and what Info-Lit skills students are likely to need. The next step is to develop the actual lesson plan.

You’re thinking, “Wait, shouldn’t we collaborate with the teacher first?” Uh, NO. In my experience, teachers who are unfamiliar with librarian collaboration can’t envision how we might help them. But, they will consider a library visit if we show them how we’ll enhance their classroom learning. Thus, we need to bring them something concrete, a printed example of how we’re using their content to teach library skills. So before approaching them, we need to build the Library Lesson Plan.

MAKE LESSONS SHORT AND USEFUL

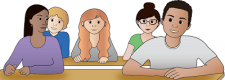

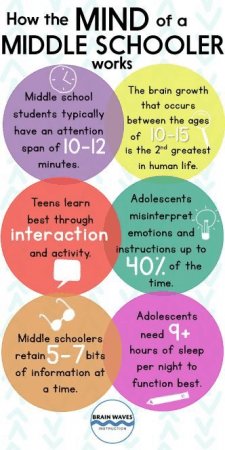

Think back to your college courses: 60 minutes, 2 or 3 a day, maybe 2-4 times per week—intervals of learning and study. Now think of your last education PD: two 3-hour sessions with a few 10-15 minute breaks and a lengthy lunchtime, and when the day is over we’re exhausted.

These two contrasting incidents are within our own discipline with which we’re familiar, yet we expect kids aged 5-18 to spend 7 hours a day, 5 days in a row, learning new information in 6 or 7 or 8 subjects with a 3-5 minute break and 30 minutes for lunch…and we wonder why they can’t pay attention and don’t remember all that wonderful stuff we tell them!

This is an even more important consideration for a Library Lesson, because we rarely see students on a daily basis. If we want students to learn and remember, we need to make each lesson memorable.

- First, teach only the information or skill they need for the task at hand.

- Second, kids remember something they DO, so give them an activity that allows them to practice what they learn.

MY LIBRARY LESSON PLANNER

Through my 25 years in classroom and library I’ve used many different lesson plan forms, depending on what the district specified, the principal wanted, the teachers used, or the library director liked. I tried all the “best” models for lesson planning, but they all had flaws when planning library lessons.

The AASL Standards for the 21st Century Learner in Action has a lesson template (p.116) that inspired me to combine the best of other planners and create my own. I’ve written about my Library Lesson Planner but its complexity can be daunting compared to other lesson plan templates. Let me take you step-by-step through it so you’ll understand what each section does and why it’s important to follow this process.

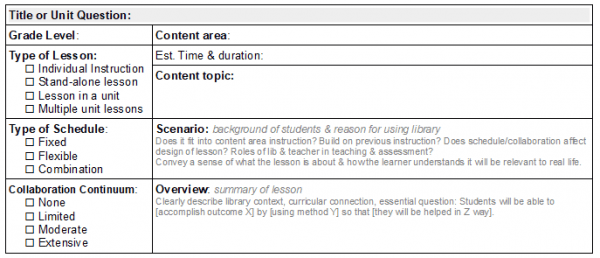

LIBRARY LESSON PLANNER – OPENING SUMMARY

The top section of the Library Lesson Planner gives a summary of the classroom topic, why students will benefit from a library visit, and what the Library Lesson is about. We use our curriculum matrix to fill out this section, because we’ve already compacted into that the information from the subject area scope and sequence document.

By starting with a clear purpose for the library visit we can keep it clearly in mind throughout our planning process. Showing just this part to an open-minded teacher could persuade them to schedule a library visit, but for most we’ll need more. It is, however, an ideal quick-planner to fill in when a teacher approaches us about a library visit. I print 2/sheet and cut in half to keep handy at the circulation desk when teachers walk in. (You can also find this on my FREE Librarian Resources page.)

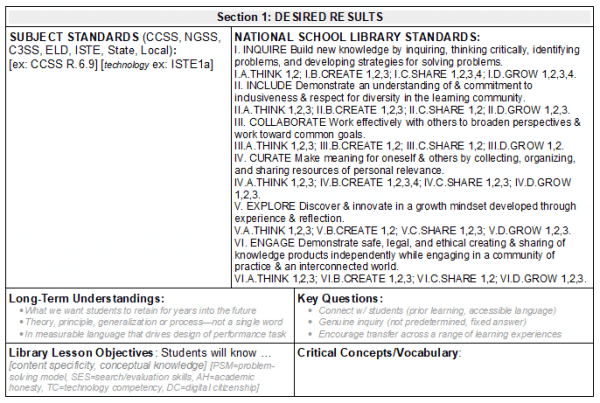

LIBRARY LESSON PLANNER – SECTION 1: DESIRED RESULTS

We know it’s important to start with the end in mind, answering the question, “What do we want students to understand and be able to do by the end of the lesson?” Begin with Subject Standards for the classroom lessons with which we’ll correlate our library lesson. (We can also add Technology Standards that apply to the lesson and/or the final product.) When we use Subject Standards as the foundation of the library lesson, we show the teacher that we are enhancing their subject material…plus it keeps us focused on integrating library skills into classroom learning.

Next enter any National School Library Standards that are pertinent to the Subject and to our preliminary ideas for the lesson. Enter more than can be completed during the actual lesson, and as you work through this section, decide which are imperative and delete those that aren’t.

From Subject and NSLS Standards, we derive the entries for each following field, incorporating at least one entry that addresses the Subject Standards, to connect what students are learning between library and classroom. Since each field builds upon the previous one, we refine the Library Lesson to those essentials of both Subject and Information Literacy that fulfill the purpose of the visit.

From Subject and NSLS Standards, we derive the entries for each following field, incorporating at least one entry that addresses the Subject Standards, to connect what students are learning between library and classroom. Since each field builds upon the previous one, we refine the Library Lesson to those essentials of both Subject and Information Literacy that fulfill the purpose of the visit.

From chosen Standards, construct 2 or 3 Long-Term Understandings; these are the “big ideas” we want students to remember and apply to future learning. From the understandings create 2 or 3 Key Questions that focus on the content needed to attain those understandings.

From the questions generate the ‘answers’ that “Students will know” by the end of the lesson, that is, the specific Content Objectives for both Subject and Info-Lit. Finally, from Objectives choose the Critical Concepts and Vocabulary to emphasize during the lesson. These last two fields—objectives and concepts/vocabulary—help us build the teaching and learning activities in Section 3, but going through this process first—Standards to Vocabulary—ensures that the lesson is truly worthwhile.

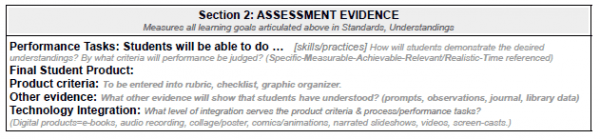

LIBRARY LESSON PLANNER – SECTION 2: ASSESSMENT EVIDENCE

How will we know the Desired Results listed in Section 1 have been achieved unless we have some evidence? More specifically, we must give the teacher something on which to base a daily grade that demonstrates student learning. This section, more than any other part of the lesson plan, will convince a teacher to collaborate with us because they now have documented accountability for “deviating” from their own lesson plan.

Performance Tasks—what “Students will be able to do”—must be specific and measurable. For this entry I still use Benchmarks from Standards for the 21st Century Learner in Action that relate to the Library Standards chosen in Section 1. I may also include Behaviors from the Dispositions or Responsibilities Indicators.

The Final Product and Product criteria may already be specified by subject curriculum or the teacher’s lesson plan. That student product may indeed be a good one; however, it’s typically conceived by teachers who don’t have the background in Information Literacy (planning, problem-solving, research, resources, media and technology) that school librarians have. Therefore, we must conscientiously fill in this section to be sure the final product and its criteria are both authentic and possible with our library resources.

We can translate Technology Standards from Section 1 into Technology Integration criteria, then add that and our Info-Lit criteria to Product criteria—teachers appreciate seeing these written down to include in their rubrics and checklists.

If it’s difficult to coordinate entries in this section, we need to reconsider what the teacher is expecting students to accomplish and suggest an alternative product. Because we use their Subject Standards as the foundation for building our lesson, new product and performance task suggestions are more readily accepted by the teacher.

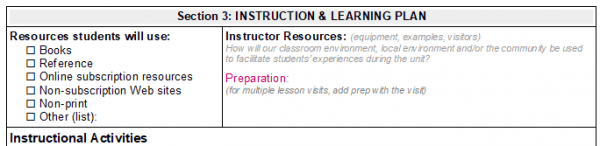

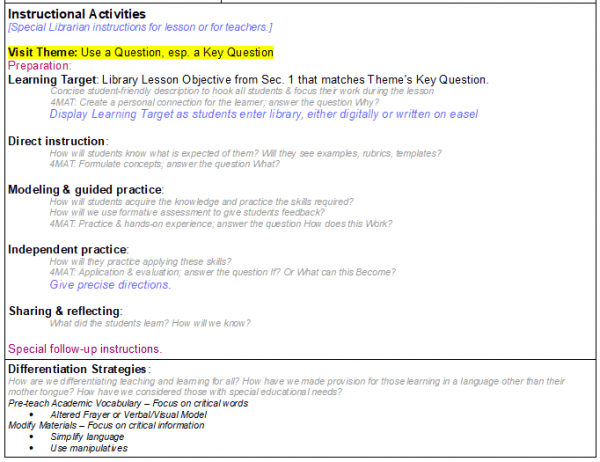

LIBRARY LESSON PLANNER – SECTION 3: INSTRUCTION & LEARNING PLAN

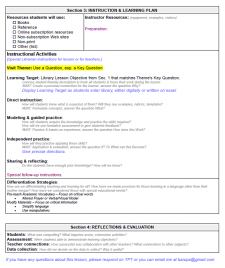

While working through the preceding sections, we’ve begun to accumulate ideas for this section, and possibly written some down. The top areas that list student resources and teaching aids, such as handouts, online sites, equipment, and examples, means we can quickly glance here the day before the visit to be sure we have everything ready when students arrive.

Now we’re ready for Instructional Activities—exactly what we teach and what students do. I like to have a Theme for each library visit, related to a Key Question. Learning Targets and Differentiation Strategies are typical requirements in most schools/districts nowadays. A learning target is simply a student-friendly version of an objective from Section 1.

Library visits are rarely contiguous, often days—or even weeks—apart, so each Library Lesson visit must cover a complete lesson cycle. The AASL Standards for the 21st Century Learner in Action template (p.116) is perfect for a library visit: Direct instruction, Modeling & guided practice, Independent practice, Sharing & reflecting.

The prompts from other lesson planning tools such as UbD, UDL, and 4MAT help me formulate my lesson activities, and I delete the prompts after I’ve completed each part. If I have a slide presentation, I use the Notes feature to write my speaking script so I only have to write the Slide# on the lesson planner with follow-up actions for the slide.

(I use PrimoPDF to convert the Notes to a PDF and print it out to use during the presentation.)

Because this lesson planner lends itself to single lesson or whole unit planning, we can use the Instructional Activities section for one or for multiple library visits. If I have multiple visits, I copy & paste a new Visit Theme-through-lesson cycle below the first, then add a number to each: Visit #1 Theme…, Visit #2 Theme….

LIBRARY LESSON PLANNER – SECTION 4: REFLECTIONS & EVALUATION

After presenting a lesson we always think of ways to make it better, so a section to record problems encountered or suggestions for improvement means we won’t forget them when we prepare the lesson the following school year.

BACKWARD PLANNING IS WORTH IT

This may seem like a lot of work for a single 40-50 minute lesson, but taking time for detailed planning—even more time than the actual lesson takes—makes a better lesson and makes us a better teacher-librarian. By starting with Subject Standards and going through each hierarchical step to the specific actions students will take, we enrich our original idea with more meaningful and authentic elements.

This may seem like a lot of work for a single 40-50 minute lesson, but taking time for detailed planning—even more time than the actual lesson takes—makes a better lesson and makes us a better teacher-librarian. By starting with Subject Standards and going through each hierarchical step to the specific actions students will take, we enrich our original idea with more meaningful and authentic elements.

A teacher will surely be impressed with our efforts, and once we’ve completed and refined the lesson, it’s useful for many years. Using the Library Lesson Planner, alongside the Library Lesson Matrix, for all our lessons can positively influence our entire school library program.

My Library Lesson Planner is available as a digital editable MS docx from my Free Librarian Resources page. If you have questions about my Library Lesson Planner or how to use it, feel free to put them in the Comments below!